What is δ, and what δifference does it make?

There are many variants or flavours of differential privacy (DP) some weaker than others: often, a given variant comes with own guarantees and “conversion theorems” to the others. As an example, “pure” DP has a single parameter \(\varepsilon\), and corresponds to a very stringent notion of DP:

An algorithm \(M\) is \(\varepsilon\)-DP if, for all neighbouring inputs \(D,D'\) and all measurable \(S\), \( \Pr[ M(D) \in S ] \leq e^\varepsilon\Pr[ M(D’) \in S ] \).

By relaxing this a little, one obtains the standard definition of approximate DP, a.k.a. \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP:

An algorithm \(M\) is \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP if, for all neighbouring inputs \(D,D'\) and all measurable \(S\), \( \Pr[ M(D) \in S ] \leq e^\varepsilon\Pr[ M(D’) \in S ]+\delta \).

This definition is very useful, as in many settings achieving the stronger \(\varepsilon\)-DP guarantee (i.e., \(\delta=0\)) is impossible, or comes at a very high utility cost. But how to interpret it? The above definition, on its face, doesn’t preclude what one may call “catastrophic failures of privacy 💥:” most of the time, things are great, but with some small probability \(\delta\) all hell breaks loose. For instance, the following algorithm is \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP:

- Get a sensitive database \(D\) of \(n\) records

- Select uniformly at random a fraction \(\delta\) of the database (\(\delta n\) records)

- Output that subset of records in the clear 💥

(actually, this is even \((0,\delta)\)-DP!). This sounds preposterous, and obviously something that one would want to avoid in practice (lest one wants to face very angry customers or constituents). This is one of the rules of thumb for picking \(\delta\) small enough (or even “cryptographically small”), typically \(\delta \ll 1/n\), so that the records are safe (hard to disclose \(\delta n \ll 1\) records).

So: good privacy most of the time, but with probably \(\delta\) then all bets are off.

However, those catastrophic failure of privacy, while technically allowed by the definition of \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP, are not something that can really happen with the DP algorithms and techniques used both in practice and in theoretical work. Before explaining why, let’s see what is the kind of desirable behaviour one would expect: a “smooth, manageable tradeoff of privacy parameters.” For that discussion, let’s introduce the privacy loss random variable: given an algorithm M and two neighbouring inputs D,D’, let \(f(y)\) be defined as \[ f(y) = \log\frac{\Pr[M(D)=y]}{\Pr[M(D’)=y]} \] for every possible output \(y\in\Omega\). Now, define the random variable \(Z := f(M(D))\) (implicitly, \(Z\) depends on \(D,D',M\)). This random variable quantifies how much observing the output of the algorithm \(M\) helps distinguishing between \(D\) and \(D'\).

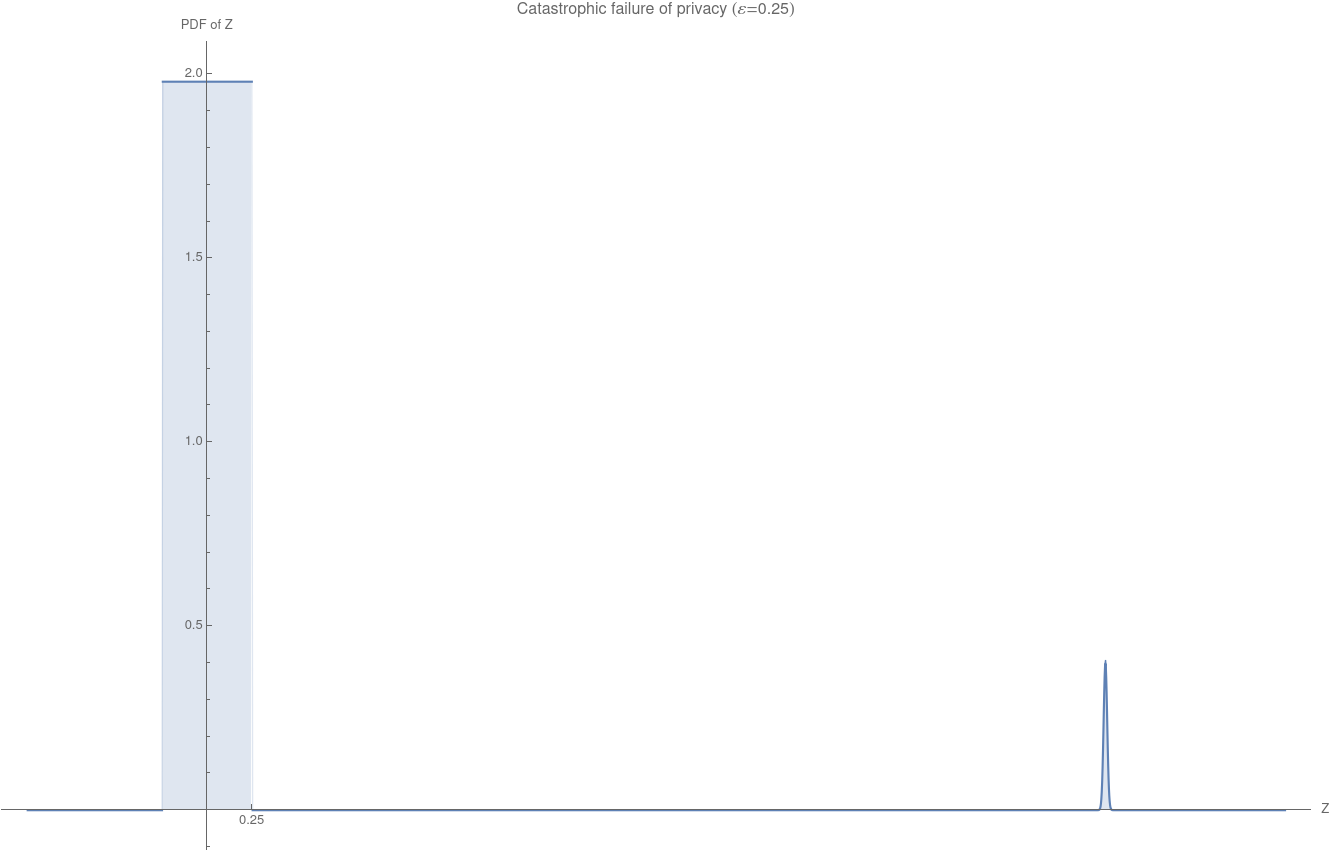

Now, going a little bit fast, you can check that saying that \(M\) is \(\varepsilon\)-DP corresponds to the guarantee “\(\Pr[Z > \varepsilon] = 0\) for all neighbouring inputs \(D,D'\).” Similarly, \(M\) being \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP is the guarantee \(\Pr[Z > \varepsilon] \leq \delta\).\({}^{(\dagger)}\) For instance, the “catastrophic failure of privacy” corresponds to the scenario below, which depicts a possible distribution for \(Z\): \(Z\leq \varepsilon\) with probability \(1-\delta\), but then with probability \(\delta\) we have \(Z\gg 1\).

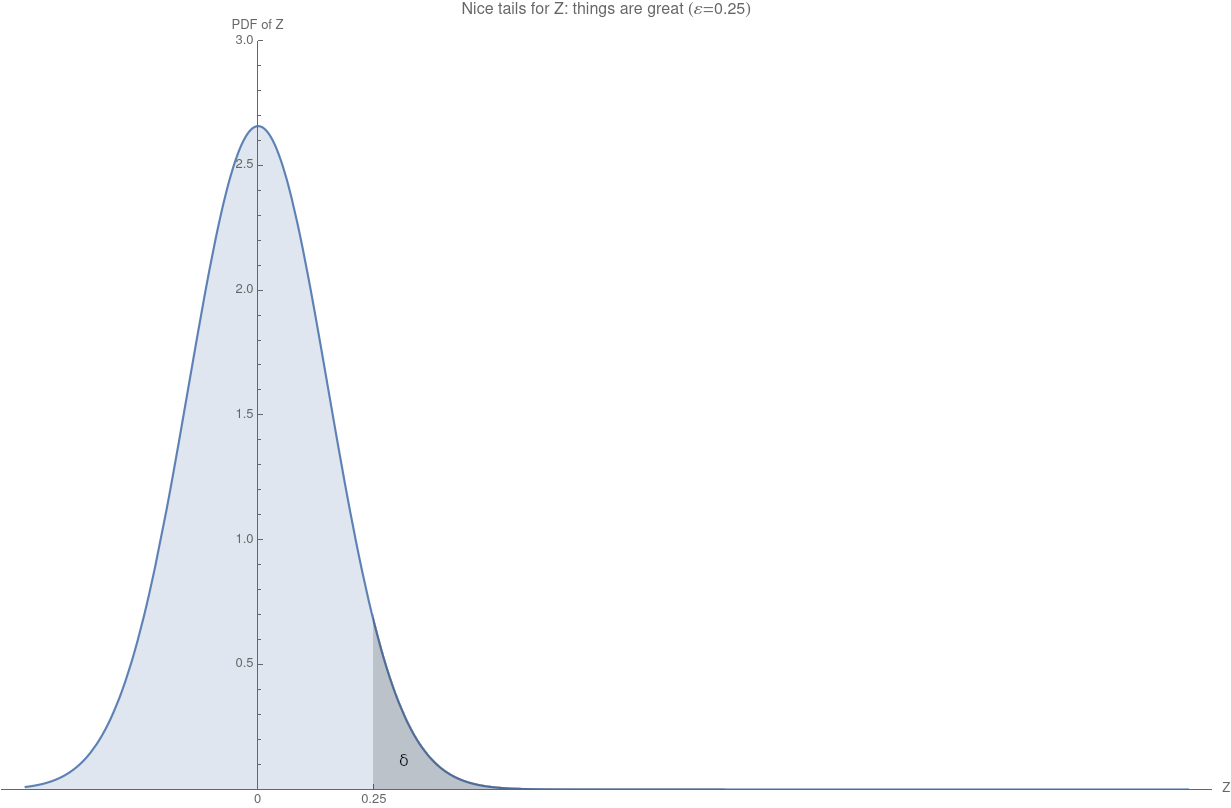

What we would like is a smoother thing, where even when \(Z>\varepsilon\) is still remains reasonable and doesn’t immediately become large. A nice behaviour of the tails, ideally something like this:

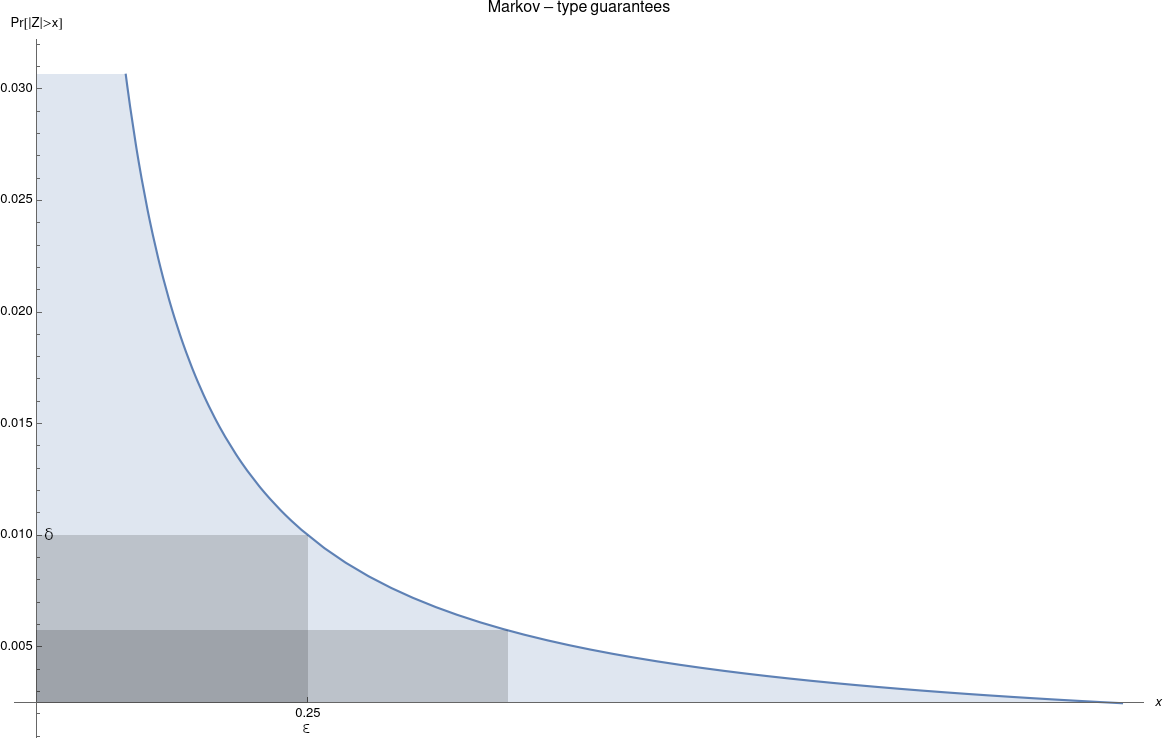

For instance, if we had a bound on \(\mathbb{E}[|Z|]\), we could use Markov’s inequality to get, well, something. For instance, imagine we had \(\mathbb{E}[|Z|]\leq \varepsilon\delta\): then \[ \Pr[ |Z| > \varepsilon ] \leq \frac{\mathbb{E}[|Z|]}{\varepsilon }\leq \delta \] (great! We have \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP); but also \(\Pr[ |Z| > 10\varepsilon ] \leq \frac{\delta}{10}\). Privacy violations do not blow up out of proporxtion immediately, we can trade \(\varepsilon\) for \(\delta\). That seems like the type of behaviour we would like our algorithms to exhibit.

But why stop at Markov’s inequality then, which gives some nice but still weak tail bounds? Why not ask for stronger: Chebyshev’s inequality? Subexponential tail bounds? Hell, subgaussian tail bounds? This is, basically, what some stronger notions of differential privacy than approximate DP give.

-

Rényi DP [Mironov17], for instance, is a guarantee on the moment-generating function (MGF) of the privacy random variable \(Z\): it has two parameters, \(\alpha>1\) and \(\tau\), and requires that \(\mathbb{E}[e^{(\alpha-1)Z}] \leq e^{(\alpha-1)\tau}\) for all neighbouring \(D,D'\). In turn, by applying for instance Markov’s inequality to the MGF of \(Z\), we can control the tail bounds, and get a nice, smooth tradeoff in terms of \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP.

-

Concentrated DP (CDP) [BS16] is an even stronger requirement, which roughly speaking requires the algorithm to be Rényi DP simultaneously for all \(1< \alpha \leq \infty\). More simply, this is “morally” a requirement on the MGF of \(Z\) which asks it to be subgaussian.

The above two examples are not just fun but weird variants of DP: they actually capture the behaviour of many well-known differentially private algorithms, and in particular that of the Gaussian mechanism. While the guarantees they provide are less easy to state and interpret than \(\varepsilon\)-DP or \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP, they are incredibly useful to analyze those algorithms, and enjoy very nice composition properties… and, of course, lead to that smooth tradeoff between \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) for \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP.

To summarize:

- \(\varepsilon\)-DP gives great guarantees, but is a very stringent requirement. Corresponds to the privacy loss random variable supported on \([-\varepsilon,\varepsilon]\) (no tails!)

- \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP gives guarantees easy to parse, but on its face allows for very bad behaviours. Corresponds to the privacy loss random variable in \([-\varepsilon,\varepsilon]\) with probability \(1-\delta\) (but outside, all bets are off!)

- Rényi DP and Concentrated DP correspond to something in between, controlling the tails of the privacy loss random variable by a guarantee on its MGF. A bit harder to interpret, but capture the behaviour of many DP building blocks can be converted to \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP (with nice trade-offs between \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\).

\({}^{(\dagger)}\) The astute reader may notice that this is not quite true. Namely, the guarantee \(\Pr[Z > \varepsilon] \leq \delta\) on the privacy loss random variable (PLRV) does imply \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-differential privacy, but the converse does not hold. See, for instance, Lemma 9 of [CKS20] for an exact characterization of \((\varepsilon,\delta)\)-DP in terms of the PLRV.

[cite this]